In 2020, The Morgan Library & Museum acquired a number of materials associated with The Black Arts Movement, which have become essential additions to our holdings of contemporary art and literature. The Black Arts Movement (BAM) was an African-American led artistic and aesthetic movement that was highly active during the 1960s and 1970s. Often called the cultural arm to the Black Power Movement, the goal of BAM was to provide positive and empowering depictions of the Black community, produced by and for Black people.

The innovative aesthetics and production methods of the BAM have heavily influenced African-American cultural production from the 1960s to present. However, these works are often difficult to find, access, and research in libraries and other cultural institutions. This is in part because BAM works disrupt our traditional standards for descriptive cataloging. Works produced by BAM artists were often created collaboratively and involved multiple media, which can complicate our traditional ideas of who counts as contributors to a work and the boundaries we draw between media categories. Additionally, there are paratextual elements of these works that are essential to their discoverability that would not typically be cataloged in more traditionally produced material.

As The Morgan engages in an ongoing review and revision of the language used in our collections catalog as a part of our Critical Cataloging Initiatives, I became interested in how critical, ethical, and anti-racist cataloging comes into play when describing materials created during the Black Arts Movement of the 1960-70s. I will focus on a specific case study of how enhancing catalog records can make these materials more discoverable to researchers, using the example of the African American visual artist Omar Lama.

******

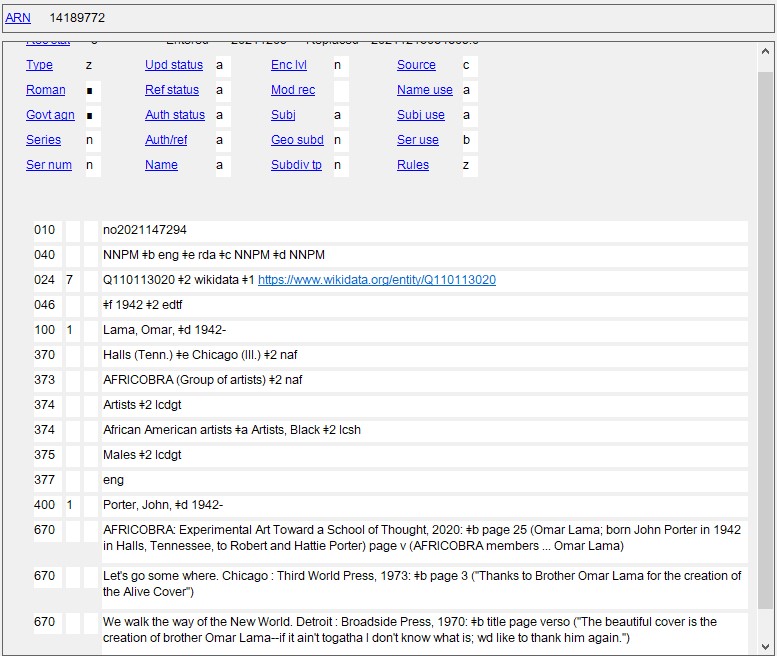

Omar Lama, born John Porter in Halls, Tennessee in 1942, is a visual artist and cofounder of Black artists’ collective AfriCobra. Lama designed multiple, seminal covers for Black Arts publications. However, I could not find his name found in any major The Library of Congress Name Authorities, VIAF, or any other major name authority file. This is likely because his contributions to the importance of these texts as aesthetic and political objects has been overlooked by catalogers.

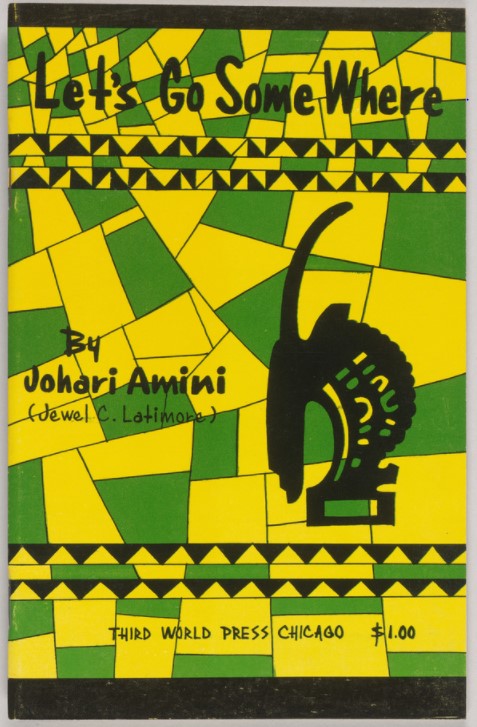

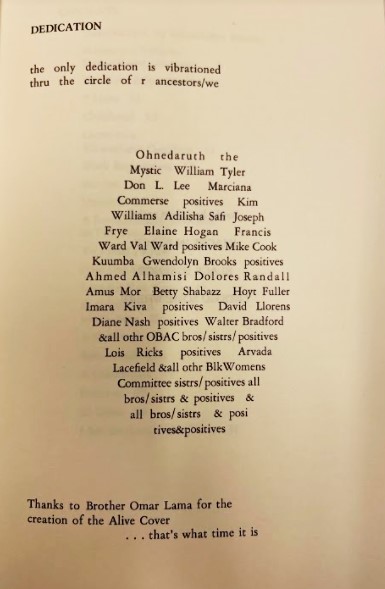

One book acquired by The Morgan, Let’s Go Some Where by Johari Amini (aka Jewel C. Latimore) has a striking cover designed by Lama featuring bold, eye-catching colors and Afro-centric imagery. However, Lama’s name is not printed in the colophon where one would usually look for publication information. Instead it is mentioned in an experimental dedication section in the text. Printed on the bottom of the unnumbered page, Amini writes “Thanks to Brother Omar Lama for the creation of the Alive Cover / … that’s what time it is”.

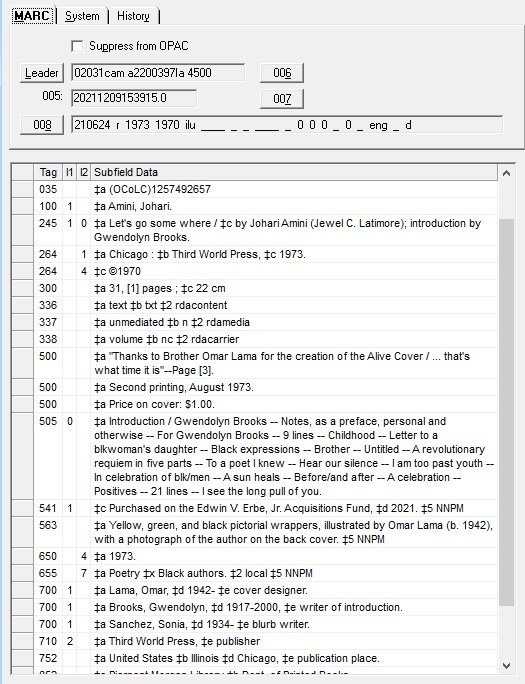

From the history of this publication, we can tell that Omar Lama’s contribution was essential to the overall feel of the publication and how the intended audience, Black readers, received the work. His connection to AfriCobra and the gratitude from the writers whose covers he designed show the collective impulse of the Black Arts Movement. Because of this, it was essential to capture these elements in the cataloging of these materials for researchers interested in BAM. I kept this in mind when creating the MARC record for Let’s Go Some Where. In addition to fully transcribing Amini’s gratitude statement to Lama in a General Note (500) for the object, I was sure to include Lama’s contribution as cover designer in an Added Entry-Personal Name Note (700).

After making sure that these connections could be made locally, the next step was to make sure that Lama’s work could be discoverable by catalogers at other institutions. In consultation with the Manager of Collections Information and Library Systems and The Morgan’s NACO Coordination, I was able to create a Name Authority File record for Lama. Using material from The Morgan’s collection as reference, I was able to add helpful information about Lama such as his place of birth (370), his occupation as an artist (374), and his connection to AfriCobra (373). This makes sure that his work can be consistently attributed when it appears in other publications.

The creation of the Name Authority File Record opened up the opportunity to create even more points of access for Lama’s work. His name can now be found in the Virtual International Authority File. Finally, using NAF and VIAF as references, I was also able to create a Wikidata entry for Lama that included more essential information in learning more about his work.

*****

This example shows how paying close attention to paratextual elements in Black Arts Movement publications can help us question, confront, and improve our cataloging practices.